|

Hurricane Winds at Landfall |

|

Hurricane Andrew was one of the most destructive hurricanes in U.S. history, tearing into South Florida in August, 1992, with sustained winds of 165 mph, and wind gusts as high as 177 mph. The hurricane destroyed over 25,000 homes and damaged over 100,000 others - primarily through wind-caused damage. Winds were strong enough to shoot this piece of plywood through a tree trunk in Homestead, FL. Image credit: NOAA. |

When a hurricane makes landfall, the shear force of hurricane strength winds can destroy buildings, topple trees, bring down powerlines, and blow vehicles off roads. When flying debris, such as signs, roofing material, building siding, and small items left outside, is added to the mix, the potential for building damage is even greater.

Threats to human safety from hurricane force winds are equally severe. Many people have been killed or seriously injured by falling trees and flying debris. This is one reason why it is important for residents and businesses to assess their property before hurricane season to ensure that landscaping and trees do not become a wind hazard. When a hurricane warning is issued, all lawn furniture and other outside objects that could become projectiles in high winds should be secured or brought inside. In hurricane prone regions, trees should be pruned each spring to remove dead and weak branches.

Hurricane winds impact homes and other buildings in two different ways: 1) differential pressures act on the building envelope, which includes roofs and walls (and their associated components), and 2) wind-borne debris may strike a building, with windows and doors the most susceptible to impact. Additionally, downed trees and power lines, being blown-down onto a building, is another way hurricanes can cause damage to structures. Rainwater damage to a building’s interior will normally result after damage to the building envelope has occurred.

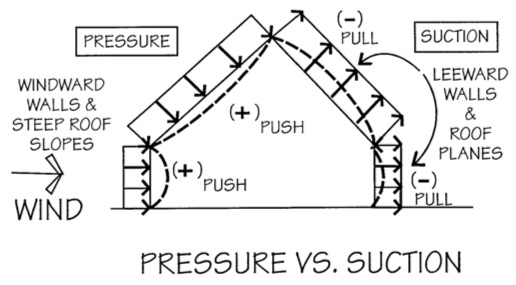

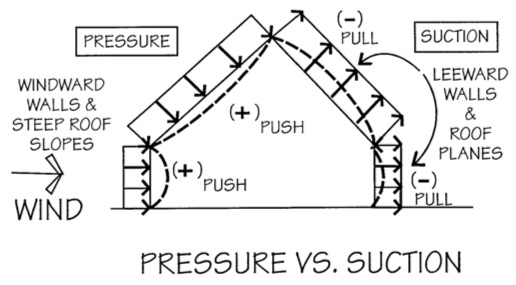

Differential pressure is defined as the difference in pressure between two points of a system, such as the opposite sides of a house or building. Excessive differential pressures caused by wind flow on two, opposite sides of any building component (roofs, walls, structural beams, etc.) could deform or dislodge these materials when the differential pressures, the more severe of which tend to be outward forcing, exceed the resistance capacities of the components and/or their connections to other parts of the building. For example, roof shingles or roof tiles can be broken or lifted off in this manner and be carried away by the wind, only to become wind-borne debris. Wall sidings, windows, skylights, and doors etc. can be damaged in a similar fashion. Even plywood roof panels or the entire roof structure can be uplifted and transported, though this normally only occurs at higher wind speeds. With a roof gone, the walls of a building are much easier to be blown down by a hurricane's winds.

As hurricane winds blows against a vertical surface of a home, such as a wall or steeply pitched roof, it exerts a positive force or “pressure” against that surface. As the wind flows over or around the home, it exerts a negative force or “suction” on the walls or roof planes parallel to or away from the direction of the wind (the leeward side). The combination of these pressure and suction forces can cause uplift (forces may strip roof coverings and sheathing or, in extreme cases, destroy the entire roof), sliding (a house may be blown straight off its foundation), overturning (and entire structure may rotate off its foundation resulting in the complete destruction of a home), and/or racking (horizontal forces cause walls to tilt and/or collapse). Image credit: My Safe Florida Home (http://www.estimating.org/mysafefloridahome/hurricane_section1.php) |

|

Wind-borne debris generated from loose-laid ground materials and/or from dislodged building components can fly an unbelievable distance, up to several hundred feet, and impact neighboring buildings. Almost all building envelope materials, particularly windows, doors and skylights, as well as most wall sidings and roof coverings used for homes, are at risk for impact from such high-energy projectiles. Breaches to the building envelope by such projectiles will allow rainwater intrusion and subsequently damage the building interior. It may also pressurize the interior of the building, increasing the uplift on the roof and the outward forces on the walls, making them more likely to fail. In high category hurricanes (e.g. category 3 or higher), wind-borne debris damage occurs essentially in parallel with the damage due to differential pressures.

Wind speed tends to decrease significantly within 12 hours after landfall (for more detail see Interaction between a Hurricane and Land). Nonetheless, winds can stay above hurricane strength well inland. For example, Hurricane Hugo (1989) battered Charlotte, NC, (175 miles inland) with gusts to nearly 161 kmph (100 mph); these winds were strong enough to topple trees and power lines across roads and houses, leaving many without power and closing schools for as long as two weeks.

Hurricane Hugo coastal damage, Sept 1989. Image courtesy of SC Department of Insurance. |

An often-misunderstood aspect of hurricane winds is the potential for increased damage as wind speeds increase. The forces against structures do not increase linearly, they increase exponentially (power of 3), and as wind speed increases.

A 241 kph (150 mph) wind is 20% stronger than a 201 kph (125 mph) wind. However, the destructive power of a 241 kph (150 mph) wind compared to a 201 kph (125 mph) wind is actually 73% greater. For example, Hurricane Andrew’s sustained winds of 165 mph were 160% more powerful than Hurricane Katrina’s sustained winds of 120 mph at coastal Mississippi.

Measuring the Severity of Hurricane Winds

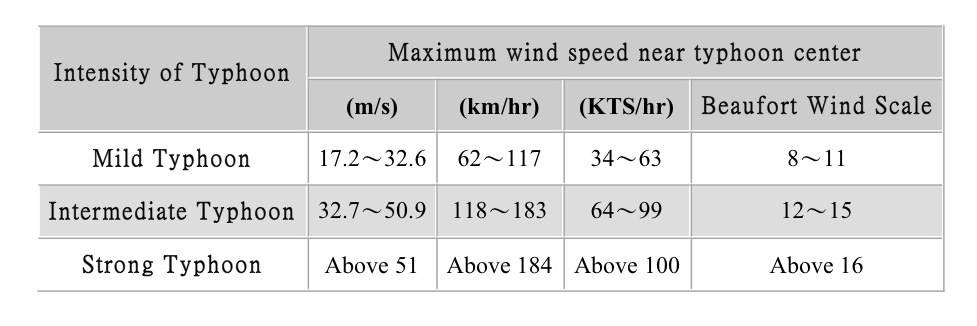

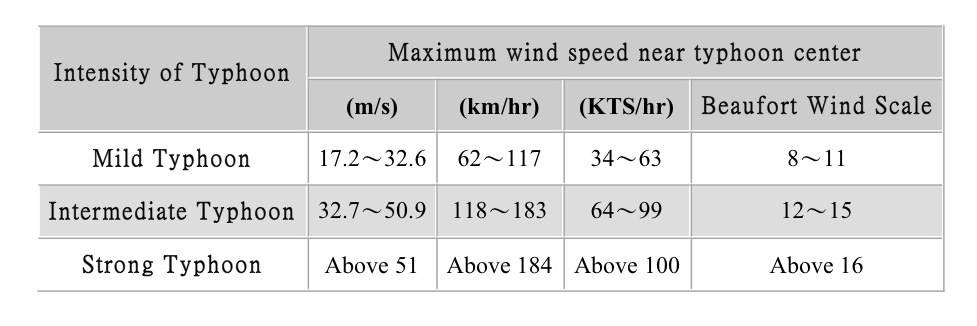

In the Atlantic and East Pacific regions, hurricane winds are categorized on a scale of 1 to 5 by the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. This scale provides examples of the type of damage and impacts (in the United States) associated with winds of the indicated intensity. In general, damages rise by about a factor of four for each category increase. Typhoons in the North Pacific Ocean (e.g. those impacting Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, and Mainland China) are also classified according to the maximum wind speed at their center.

Typhoon Scale used by Central Weather Bureau, Taiwan. Note, a Tropical Depression (TD) has wind speeds less than 17 m/s (38 mph) |

|

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale does not address the potential for such other hurricane-related impacts, such as storm surge, rainfall-induced floods, and tornadoes. It should also be noted that the general wind-caused damage descriptions are to some degree dependent upon the local building codes and how well and how long they have been enforced.

Hurricane wind damage is also dependent on other factors such as the duration of high winds, change of wind direction, amount of accompanying rainfall, and condition of affected structures. Depending on circumstances, less intense storms may still be strong enough to produce significant damage, particularly in areas that have not sufficiently prepared in advance of the storm. For more information about the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind scale, as well as the different stages of hurricane development, please see the section on a Hurricane's Life Cycle.

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale

| Category |

Wind (km/h) |

Wind (mph) |

Description |

| 1 |

119-153 |

74-95 |

Very dangerous winds will produce some damage. Flying or falling debris could injure or kill people and animals. Older mobile homes could be destroyed. Newer mobile and frame-construction homes, apartment buildings and shopping centers can sustain exterior damage (i.e. roof, siding, gutters). Flying debris can break windows in high-rise buildings- falling and broken glass will pose a significant danger. Some damage to commercial signage and fences will occur, large tree branches will snap and shallow- rooted trees can be toppled. Extensive damage to power lines and poles will likely result in power outages that will last a few to several days. |

| 2 |

154-177 |

96-110 |

Extremely dangerous winds will cause extensive damage. There is a substantial risk of injury or death to people and animals due to flying and falling debris. Older mobile homes have a high chance of being destroyed and flying debris generated can shred nearby homes. Newer mobile and frame-construction homes, apartment buildings and shopping centers can sustain major exterior damage (i.e. roof, siding, gutters). Flying debris can break windows in high-rise buildings- falling and broken glass will pose a significant danger. Commercial signage and fences will be damaged if not destroyed, shallow- rooted trees will be snapped or uprooted and block roads. Near-total power loss is expected with outages that could last from several days to weeks, and potable water could become scarce. |

| 3 |

178-209 |

111-130 |

Devastating damage will occur. There is a high risk of injury or death to people and animals due to flying and falling debris. Older mobile homes will be destroyed and most newer mobile homes will sustain severe damage, including potential roof failure and wall collapse. There will be a high percentage of roof covering and siding damage to well-built frame-construction homes, apartment buildings and shopping centers. Isolated structural damage to wood or steel framing can occur. Numerous windows will be blown out of high-rise buildings- falling and broken glass will pose a significant danger. Commercial signage and fences will be destroyed, many trees will be snapped or uprooted and block roads. Electricity and water will be unavailable for several days to a few weeks after the storm.

|

| 4 |

4210-249 |

131-155 |

Catastrophic damage will occur. Large amounts of windborne debris will be lofted into the air. There is a high risk of injury or death to people and animals due to flying and falling debris. Older mobile homes and a high percentage of newer mobile homes will be destroyed. Well-built homes can also sustain severe damage with significant losses to roof structures and/or some exterior walls. Extensive damage to roof coverings, windows, and doors will occur. Top floors of apartment buildings will sustain structural damage, steel frames in older industrial buildings and older unreinforced masonry buildings can collapse. Most windows will be blown out of high-rise buildings- falling and broken glass will pose a significant danger. Commercial signage and fences will be destroyed, most trees will be snapped or uprooted and power poles down. Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months, long-term water shortages can be expected, and most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.

|

| 5 |

249+ |

155+ |

Catastrophic damage will occur. Large amounts of windborne debris will be lofted into the air. There is a very high risk of injury or death to people and animals due to flying and falling debris. Almost all mobile homes will be destroyed. A high percentage of frame homes will be destroyed, with total roof failure and wall collapse. A high percentage of industrial buildings and low-rise apartment buildings will be destroyed. Complete collapse of older metal buildings can occur and most unreinforced masonry walls will fail which can lead to building collapse. Nearly all windows will be blown out of high-rise buildings- falling and broken glass will pose a significant danger. Nearly all commercial signage and fences will be destroyed, almost all trees will be snapped or uprooted and power poles downed. Fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months, long-term water shortages can be expected, and most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.

|

References

Additional Links on HSS

|

|